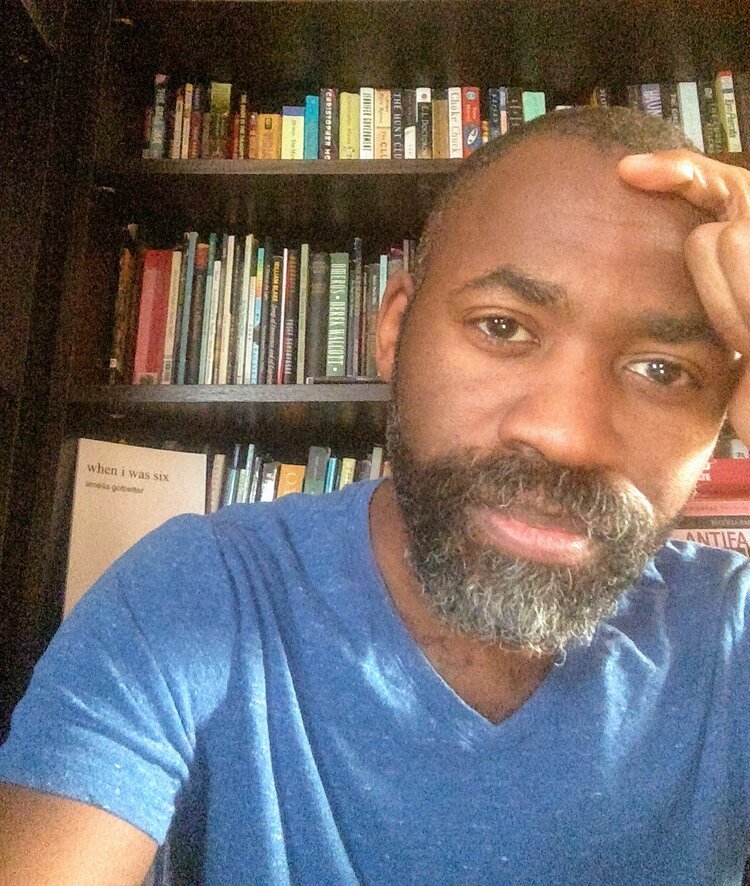

Interview with Matthew E. Henry, Author of the Colored page

Matthew E. Henry (MEH) is the author of the Colored page (Sundress Publications, 2022), Teaching While Black (Main Street Rag, 2020) and Dust & Ashes (Californios Press, 2020). He is the editor-in-chief of The Weight Journal and an associate poetry editor at Pidgeonholes.

MEH’s poetry and prose appears or is forthcoming in Barren Magazine, Fahmidan Journal, The Florida Review, Massachusetts Review, New York Quarterly, Ninth Letter, Ploughshares, Poetry East, Shenandoah, Solstice, and Zone 3 among others. MEH’s an educator who received his MFA yet continued to spend money he didn’t have completing an MA in theology and a PhD in education. You can find him at www.MEHPoeting.com writing about education, race, religion, and burning oppressive systems to the ground.

Matthew E. Henry's poetry collection, the Colored page, was released in July 2022 from Sundress Publications. He sat down to answer questions on microaggressions in education, poetry form, and character authenticity.

Jacquelyn Scott: Congratulations on your new poetry collection, the Colored page! What inspired these poems?

Matthew E. Henry (MEH): Thank you! I was working on a collection of persona poems that wasn’t going anywhere. When I started pulling out the poems I was most drawn to, I saw that they were largely based on my experiences in the classroom, on both sides of the desk: as student and teacher. The basic outline of the collection formed from there.

the Colored page is the semi-autobiographical journey of a kid often being the only Black or Brown face in a classroom, a school building, or an entire school district. From first grade through doctoral work, from student to teacher. Thus, the collection is presented in chronological order, from elementary school through the fairly recent past (to the dismay of people who see themselves in the texts).

Scott: What would you like the biggest takeaway for your readers to be from the Colored page?

MEH: I want readers to see themselves in these poems, from one vantage point or another. Some see themselves because they have experienced these stories personally. They have been the ethnic or racial minority, dealt with microaggressions and outright aggression, or been “othered” in a variety of spaces. I want these people to feel seen and validated. To know they are not alone in the presence of gaslighting and those who told them that they should simply keep their heads down and not make a big deal out of things.

The other audience are those who see themselves as the conscious or unconscious perpetrators of those types of actions. What people in this category do is out of my control, but I’d like to think some of them begin to reassess the ways in which they walk through the world and interact with others different from themselves.

Scott: How has your writing or your writing process changed since your first collection?

MEH: My first collection was Teaching While Black, from which a handful of the poems in the Colored page were taken. In that way, the writing is very similar in terms of themes and compositional style. Most are school-based and often written in the first person, and/or is a direct address to someone else. However, my second collection, Dust & Ashes, is thematically and inspirationally different.

Dust &Ashes is a meditation on the concept of mento mori: we’re all going to die, so what are we doing with the time that we have? Furthermore, it loosely and spiritually follows the progression of the two testaments of the Protestant Christian Bible: the Hebrew Bible and the Christian New Testament. As such it employs religious characters, stories, and metaphors that have wrestled with the idea of our impeding shuffling off this mortal coil, though historical and pop culture references also abound. To that end, and of special note, each poem in the collection pays homage to another work of literary or visual art. It includes poems inspired by the paintings of Cabanel, Delvau, and Hopper, modern photographs, and a 13th-century Japanese sculpture. The prose of Jeanine Hathaway, Toni Morrison, and Flannery O’Connor are muses for this collection, as much as poetry by Eliot, Frost, Rilke, and Sexton. Greek myths, Grimm fairy tales, and (of course) the Bible, among others, also make appearances.

Scott: What is something you’d like to try in your work that you’ve never done before?

MEH: I need to experiment more with form. When I’ve stuck my toe in the formal world, I always end up bastardizing a form to fit what I want, instead of seriously engaging the discipline of fitting my thoughts to the form. I have a collection of sonnets coming out next year, but I’m sure Shakespeare and Petrarch would roll their eyes at them, to say nothing of the pantoum-adjacent poem I’ve published.

Scott: When did you discover your gift for writing, and when did you start calling yourself a writer?

MEH: I started writing short stories in the first grade, mostly as a way to process my new situation: being at a new school and the only Black kid in my class of rich white kids in the suburbs. Though the stories weren’t about race, that was definitely the impetus for my writing. I wrote a series about Double-O Mouse: spymaster and crime fighter. All the characters in the stories came from people in my life. Friends were good guys, enemies were bad guys. This continued throughout most of middle school and into high school. Some classmates actually wanted to read what I came up with, especially to see who I praised and who I threw under the bus. In high school, I became more “serious” in my writing, branched out my prose. I tried to tackle deeper topics, most of which I can’t even remember now. I just know it was bad writing. I even attempted to start a few novels.

In college, I took a creative writing class, which is where I discovered poetry. My ADHD behind could tell a story without having to labor over exposition and character development? This sounds like heaven. It would be almost 20 years until I wrote a short story again. That was around 2000. My poetry started finding homes in journals around 2003 or 2004. My first chapbook was published in 2020. My first full length in 2022.

A couple of weeks ago, I was Zooming into a creative writing class as a guest speaker. They also asked me when I started to consider calling myself a writer. My answer is still the same, “about a week ago, if ever.” I write and sometimes people want to read it. I guess that makes me “a writer,” but I’m not sure.

Scott: What writers did you enjoy reading as a child?

MEH: Whatever was close at hand. Because they highly valued education, my immigrant parents spent stupid amounts of money buying books for my older siblings, especially from the Scholastic Book Fairs. Those books were eventually handed down to me. So I read everything and anything I could get my hands on from the Encyclopedia Brown series, to actually reading the two sets of encyclopedias we had on the shelves. Specific books I remember reading for fun during my elementary school years, and which were seminal in various ways to me, include (in no real order) Spinelli’s Maniac Magee, Juster’s The Phantom Tollbooth, Hamilton’s Many Thousands Gone: African Americans from Slavery to Freedom, Dumas’ The Three Musketeers, Nelson’s The Girl Who Owned a City, and Kennedy’s The Rise and Fall of Ben Grizzard.

Scott: What are you currently reading or working on?

MEH: My second full-length collection (The Third Renunciation) is due out next Spring from New York Quarterly Books, and I have another chapbook (said the Frog to the scorpion) due out next Winter with Harbor Editions, so polishing both of those are consuming a chunk of my mental space.

I’m still drafting and revising individual poems unattached to any project, though I have another three chapbook ideas floating around in the back of my head. But I’ll get to those in due course. For some reason, I continue to dabble in prose and am currently revising a handful of creative nonfiction and fiction pieces, hoping to find them a good home.

Scott: What is the best piece of writing advice you’ve received?

MEH: That the languages and images employed, especially for emotionally fraught situations, need to be authentic to the characters, even when the words needed are outside of my comfort zone.

During my MFA I wrote a poem about a story one of my students told me. He had encountered a woman he believed was abused, called the police, and was subsequently cursed out by the woman and harassed by the police for his efforts. Because I don’t engage in a lot of swearing in my own life (at least at the time), my early draft of the poem used painfully clever language and disguised images to describe the woman and her words to my kid. My professor at the time (the wonderful poet and person Jeanine Hathaway) told me that I was doing more/additional violence to this woman, further silencing her fear and rage by not using her words, showing what had happened to her. Even if I didn’t feel comfortable with those words or those images, they were true to the experience and I needed to capture those as accurately as I could.

Words and images are often stark because there is something we can learn from them if we move beyond our shock or offense at being confronted with our inhumanity. As anyone familiar with my writing can attest, this is a message that stuck with me.

From Sundress Publications:

the Colored page by Matthew E. Henry

At the center of the Colored page, there is a reckoning with the racism written into the pages of America, and Henry leads us from the microaggressions of educational oversight, to the horror of blatant dehumanization. In pieces that directly call out those responsible—educators, institutions, and peers alike—the speaker moves via Henry’s generously vivid poems through open letters, vignettes, and poetic narratives that uncover the realities of an educator’s life’s work in the “United” States today. Here we see the impact of ferocious racism and its brutal cousin, weaponized incompetence.

In a world that so often seeks to minimize Black experiences, the Colored page does not inflate, but neither does it look away. Yet, too, there is joy in these pages. Henry invites us to love, but please don’t touch, the beauty of Black hair, of Black lives, and of our Black students. For as much as he shines that telling Black light on the stains of the institutions he has spent his life within, Henry here evidences a life well-lived, a life spent studying, growing, and thriving despite the biased budgeting and the crude mishandling of student dignity. Henry asks us to look at the vile and call it out, but then we are tasked to shift our focus to the glory that is the student who triumphs. Henry invites us, ultimately, to a celebration.

Get your copy from Sundress Publications.

Do you have suggestions on who I should interview next, or would you like to be featured? Send me a message or find me on social media.